The Stranger, Star Dust, and Deer

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

The Waste Land. V, What the Thunder Said

This is the third time; I hope good luck lies in odd numbers….There is divinity in odd numbers, either in nativity, chance or death.

Shakespeare: The Merry Wives of Windsor

After fourteen years teaching high school, year fifteen will be my first under a new department chair. That this was unusual hadn’t sunk in until I told a peer who laughed and said it would be his sixth, no, no, seventh in twelve.

She had hired me, given me my chance in education and come to be a good friend. She was respected within the department and throughout the school for her work ethic, mentoring, leadership, money spent out-of-pocket, and sacrifice of personal time. Or so I’d thought. I’d learned of her departure Memorial Day weekend in a hotel in Highlands, N.C., a favored mountain getaway where my wife and I hike the Nantahala Forest, stroll the shops, and dig in to sweet and savory breakfasts. We’d just checked in, late afternoon. I was looking forward to the unwind after weeks of proctoring exams and finalizing grades. I can still picture the view from the warm concrete balcony – one of those “where were you when you heard” moments – feet on the iron rail, sun sprayed through the treetops, a honeysuckle perfume mixed with orange light sifted through a flurry of helicopter seeds, sycamores channeling the traffic sounds of Highway 64, popping choppers and chuffing campers and grinding trucks all magnified up the mountainside. I cupped my hand to the phone straining to hear, parsing the unfathomable. That night, I slept in a fit. The only boss in education I’d ever known had resigned abruptly under circumstances one might call sub-optimum.

At least summer vanished as expected.

First day of school commute, 2019. I lock the front door, step into the dank air between geraniums craning from two rotund planters guarding our porch like marble lions, past the mailbox, flap open, and onto the street where I’m startled by a stranger. Practically walk into him. He’s hooded, dead center of the street, backlit by a lone streetlamp. A cavity where his face should be.

“Good morning,” I say, as neighborly a tone as possible for 5:45am. He passes in silence. Odd. An ill-advised believer in mankind and their vehicles, I think, like my wife, stubbornly choosing the middle of the street in a misplaced bliss, a reckless state of deprivation – ears stuffed with ear buds. Why else no greeting? But I hear no tinny buzz. Maybe he is an early-bird retiree, absent buds, just poor hearing, somebody’s granddad. His age, really, I can’t tell. Maybe English not his native tongue, reluctant to give voice.

Typically, out the door, I’d scan up and down the street before sliding the deadbolt. A summer out of practice, I’d totally missed him.

Recently, Cheryl had read on NextDoor app of stolen mail in the neighborhood, sightings of a strange man on foot.

Of Malcom Gladwell’s just released, Talking to Strangers, the New York Times reviewer writes, “Gladwell’s main conclusions are that it would be disastrous if we stopped trusting people, that we should ‘accept the limits of our ability to decipher strangers,’ and that it behooves us to be thoughtful, humble and mindful of context when trying to understand people’s actions.”

Talk to strangers – suggests Richard Wiseman in The Luck Factor, “Lucky people are magnetic socially. Lucky people smile twice as much as unlucky people and engage in eye contact.”

I cannot confirm whether this stranger – medium build, sweat pants, no face – is smiling. I’m not. He’d seen me exit my house at an odd hour. Walking on, I couldn’t shake the thought, had I locked the front door?

Uneasy thoughts shift to the upcoming school year. Many faculty are strangers to me. Teaching is mostly a solitary endeavor, hallway greetings a courtesy, the smallest bridge to connect. Pleasantly greeting the unacquainted is a value not all share. I sneak a peek at them, the eye-contact unwilling, their disinterested faces, and wonder – is it a lack of shared values or is it confidence, a lack of social grace, or something else? A harbored secret? When I pass our principal in the hall, greetings exchange, but otherwise, the most we ever really share is auditorium air at faculty meetings.

The sidewalk worries me. Privet hedge on one side, a row of maples on the other, perfect anchor points for a spider’s web. Picture the Gary Larson cartoon panel: two spiders at the bottom of a playground slide, astride their giant web stretched across the slide’s mouth, as up above a hefty boy settles in, one spider turns to the other and says, “Pull this off, we’ll eat for days.” Recently, I was surprised and pleased Cheryl had accepted my pleas to stay on the sidewalk, at least while zoned out to her Audible books. She walks with her back to traffic, queen of the neighborhood. She’d received comments from concerned neighbors, “We can’t see you,” and finally gave in, changing her morning middle-of-the-road strolls, hoping my predawn commute would clear her way of all silken clotheslines. It was not in me to confess I share the fear and walk the street too.

Per Ojibwe legend, spiderwebs were protective charms. The Ojibwe handcrafted their own webs, weaving together twigs and string strung across a hoop, suspended above a newborn’s crib. You’ve seen their slick, commoditized versions sold in Native American-themed gift shops: dreamcatchers. The Ojibwe draped real spider webs on their handmade hoops, to “catch any harm that might be in the air.”

Past the stranger, heart rate up, I walk north along a corridor of maple and pin oak and through the canopy I locate the north star, Polaris, per my morning routine, when right then, a brilliant white streak slashes down, a vertical gash in the sky. The painted blaze burns a second or two longer than most – a shooting star.

The problem of witness to a shooting star is threefold – isolation, brevity and magnificence – so astounding, so supernatural, I immediately question its occurrence: a trick of the retina? I’m alone. No one to ask, did you see that? I’ve come to learn a retreat of vitreous gel can signal the brain to “see” false flashes. Vitreous degeneration is caused by growing old, those above 50 most affected.

But no, I’ve seen it. Wider, farther, a clear fall from heaven. A good second! Special. It feels right, seems significant, first day of school and all. But the meteoric uplift is brief. Something like cold fills my chest, the firmament’s rip seems to convey a cosmic sluice down my throat, a polar pour of anti-matter that frosts my insides. Ahead there is something. I look at a cypress in a backyard, and see a tendril of vapor (or smoke?) coiling around the feathered limbs that extend like unwanted handshakes, the smoke rope winding deeper, strangling the rusted trunk. The decayed bark and spiky internals are reminders that even hulking trees require defenses. I check my surroundings for I don’t know what and consider cutting back the Netflix binges of Stranger Things.

A non-science entry, an odd branch, on howstuffworks.com titled “Ten Superstitions about Stars,” number nine,

Superstition reveals that pointing at the stars can be just as frowned upon as pointing at a stranger on the street. The legend stems from the ancient belief that the stars were actually gods or other supernatural beings peering down at Earth from the heavens. Pointing at a star, therefore, meant you were actually pointing at a god. This could anger the god, bringing unwanted attention and bad luck down on the pointer and his or her family.

Some cultures saw shooting stars positively, the sign of a healthy newborn blessed upon earth.

There’s a world birth every eight seconds per the rotating tumbler on the census population clock. Presumably, the tumbler does not spin faster every August as Earth passes predictably through the icy dust tail of the Swift-Tuttle comet.

Out of the neighborhood I check for a more pressing danger – roundabout traffic – before crossing to the east side of Route 372. Ahead, a sprawling oak sends limbs far, shading the highway west, dropping acorns east on pedestrians. Beneath the oak are two deer grazing acorns. I spot them first and stop, watching, pretending I am one in the wild too, in my pressed shirt, Patagonia messenger bag slipping from my shoulder. It holds my day’s ration – thermos of coffee, cheese sandwich, two macadamia nut cookies. I can see their jaws working.

The oak marks my halfway. Ancient cultures revered the oak. I pay my awe and gratitude to its suburban magnificence daily, an ecosystem in itself, spooky in the morning, cool and refreshing in the afternoon, the favorite part of my commute.

Apparently, deer shell acorns before swallowing, their browsing prevents an overdose of tannins – toxic enough to cause gastric problems, kidney damage, and death in gluttonous, non-browsing cattle that lack healthier forage. Centuries ago, Native Americans would ground acorn for gluten-free flour, careful to leach the bitter tannins first.

In Norse mythology, Thor rode out a terrible storm beneath an oak, which led to the Viking practice of placing acorns on windowsills to ward off lightning, thought, in ancient times, to enter through windows. Why the god of thunder might seek refuge from a storm is left unexamined.

From experience I know the deer will dart one of two ways: east toward the safety of the middle school and expanse of tended lawn; or west, risking the highway, the lucky leapers escaping into five acres of undeveloped deciduous forest, their sanctuary on sale for over a decade now.

I make my gambit, leave the sidewalk onto a grass berm to outflank the skittish pair, to push them toward the middle school. Jumpy, risking traffic myself, I watch as they turn tail and bob – no! – north, parallel to the highway, losing sight as the landscape crests and dips, the deer disappear behind scrub that fails to obscure the menace, a southbound approach of high-beams. The deer reappear, pivot, panicked, a doomed path west to transect the cones of ghost blue. My breath catches, time slows beneath the oak. Above the crescendo of worn truck tire, I distinguish three frequencies of cricket, an earthy scent, parsley, anticipate the screech, stench of scorched tread, crunch of grille on ungulate. I consider a possible future, whether I’ll stay, present myself to the distressed motorist – unsure of any moral obligation to admit my role – or slink away in the dark to where the cursed deer should’ve run, the other goddamn way toward the middle school.

Tribe elders met in the shade of the sacred oak in hopes the tree would grace them with wisdom.

I cannot pinpoint the deer through the brush, but I am convinced one will die.

Once Meursault, the condemned man in Camus’ novel The Stranger, gave up hope that his inept lawyer would discover a loophole or avenue for his appeal, the guillotine no longer seemed a noble way to die. Lying on a cot in his prison cell, the horrifying sounds Meursault imagined of his executioners impending approach – they always came for you in the predawn – finally relented. Meursault’s fantasies and fears abated once he abandoned all hope for freedom, for meaning. After forfeiting his search for significance, only then did he find the way to live.

The truck nears, barreling like thunder. Where are the deer? I stop wishing for luck, wings, a miraculous vault. I move forward to accept my grisly role, oddly at ease, just as the truck speeds past, no hint of braking. As if the deer were never there. I peer into the woods where I think they go, but see, hear nothing. Like they passed straight into a parallel universe. I don’t get it. Did the driver have no time to react, the deer escaping death by the hair of their bobbing white tails? Like shooting stars, the deer have vanished, but unlike the burn of comet dust, it takes time, days rather than seconds, before I begin to doubt whether they were ever really there.

The high school pillars are in view, cast in the blinking glare of the front lawn’s brick-mounted LED sign, an edifice to last the ages, flashing ads for Olde Blind Dog Pub, ‘Cue, a barbecue joint, and a community credit union. I wipe my slick forehead, stick a finger to free the collar from my clammy neck and contemplate events of three – the stranger, star dust, and deer – their neat and tidy meaning, when I look down at an odd-shaped rock or curled leaf on the sidewalk. I toe the rock, deforms a bit, refuses to hop. A toad.

Toads and frogs are associated with witches, bubbling cauldrons, and magic. I like their duality, amphibians, adept in air and water, semi-permeable skin, a membrane allowing water vapor to pass directly from air into their body. Toads represent change or metamorphosis, an ability to adapt to more than one environment. Life never too sticky for a toad.

Change is good. On the other hand, there’s the moral of Grimm’s fairy tale, The Three Feathers. A dying King wished to bequeath his kingdom to one of three sons. To decide, the King tasked each to return with a beautiful carpet; the King blew three feathers in the air and said, “You shall go as they fly.” One feather flew east, one west, the third fell at his feet. The two elder brothers rushed off east and west while the youngest was left where the third feather fell.

Near the fallen feather, the youngest son found a trapdoor in the earth. Down a stair to an underground room sat a great fat toad. The simplest son said, “I should like to have the prettiest carpet in the world.” The toad took from a box an unearthly beautiful woven carpet. The two other sons, underestimating their simpleton brother, brought back coarse handkerchiefs from the first shepherds’ wives they met. The King awarded the kingdom to his youngest son.

But the elder sons argued the kingdom could not be left to their foolish kid brother. The King blew the feathers into the air again, requesting “the most beautiful ring.” The elder brothers went east and west, the youngest stayed and the fat toad gave him a jeweled ring, sparkling beyond all earthly goldsmiths.

The two older boys returned with an old carriage ring they’d pried nails from. The King awarded the kingdom to his youngest. But the eldest sons’ whined again, so a third challenge, “bring back the most beautiful woman.” Three feathers blew. The simple son visited the toad who said, “she is not at hand but here, take this hollowed out turnip,” to which six mice were harnessed. The son said, “What am I to do with that?” The toad said, “Just put one of my little toads in it.” A little toad was placed, instantly turned into a beautiful maiden, the turnip a coach, the mice into six horses. The eldest sons returned with the first peasant girls they’d met. The King awarded the kingdom to the youngest.

After three quests, you’d think, a perfect time to end the tale. But no.

The eldest convinced their father to a fourth, final contest: the wife who could jump through a ring hung in the center of the hall should get preference. The eldest sons contrived, “The peasant girls can do that easily; they are strong from work, but the delicate maiden will jump herself to death.” Their plan failed. The stout peasant girls fell, broke bones. The pretty maiden “sprang and sprang as lightly as a deer.” The youngest earned the crown. And ruled wisely.

So don’t stray. Don’t change. To the simple go the spoils.

Weeks pass. At home after school on tv: a man arrested for a traffic offense the next county over was found with mail from the city of Milton scattered in the backseat of his car. Mail I hadn’t missed mid-August reconstitutes as a beam of electrons sometime around Labor Day.

Even after I’d condemned the totemic animals to doom, the two deer keep reappearing from the wood on my commute like spirits, seeming to bear no ill will.

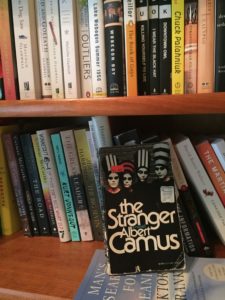

Holding an absurdist paperback four decades old appeared to my wife very strange.

I’d first read Camus’ The Stranger in high school. I still have the paperback, pages yellow, stiff, musty. The prisoner-clown-mime cover art weird enough for Cheryl to ask, “What are you reading?” Shelved below my Gladwell books. I read it in three sittings, alternating the book every fifty pages or so with a recent Barnes & Noble purchase, Man’s Search for Meaning, by Victor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and survivor of four Nazi concentration camps. Frankl had the chance to leave Europe prior to the Nazi sweeps, but stayed to care for his elderly parents. Ultimately, Frankl’s parents, his wife, and his brother died in the camps.

A meteor that enters the atmosphere at a low angle takes longer to heat up, leaving a longer swath of light before flaming out. More resistance, a plow through more air, means more light.

Frankl said the technique that aided his survival was imagining a future lecturing about his camp experience.

My department chair had plowed through two decades of environmental science lecture before her final flame out.

Frankl’s insight: never abandon hope, invent a meaning, suffering is meaningful. And Camus’: nothing is meaningful, look for significance and find it, in nothing.

The Camus and Frankl books – differing font, differing page size, differing word counts per page, differing philosophy – each concluded with the same page number: 154. Huh. Now what could that mean?